On March 6, 1957 a 47-year old man commanded the attention of the entire world as he declared the birth of a new nation.

“At long last, the battle has ended! And thus, Ghana, your beloved country is free forever!”

Dignitaries from 72 nations across the world, including US Vice President Richard Nixon, will troop into this tiny West African nation for this event and the days of celebration that followed it. Six hundred reporters and photographers will stumble across the country trying to capture this historic event. US Civil Rights activists and music stars will be part of the throng of people rushing not to be left out.

Who was this man? How did he come to stand on this stage in front of thousands of adoring people who were shedding their identities as British colonial subjects and adopting a new, untested identity? And most importantly, why did the world care so much about him?

Francis Nwia Kofi Nkrumah was born in Nkroful on September 21, 1909 (or was it 1912?) to parents of extremely modest means even by the standards of an early twentieth century British West African colony. Despite this, he would go on to be educated in the United States and subsequently rub shoulders with the cream of the local elite of the Gold Coast.

Investigating this improbable tale is one of the main tasks that African American journalist and author, Howard French, undertakes in The Second Emancipation. Coming in the wake of his critically acclaimed Born in Blackness (2021), French tries to piece together the life of the man who became known to history as Osagyefo (Dr) Kwame Nkrumah through a forensic examination of contemporary sources and the (badly preserved) historical artifacts associated with the man and his government.

The book is structured in three parts – the first part follows the development of anticolonial and black nationalist theory through often overlooked pioneers like Africanus Horton, Martin Delany and Edward Blyden. And then to more widely known giants such as WEB duBois, JE Casely Hayford, and Marcus Garvey. This section also follows Nkrumah’s early years from the Gold Coast to his study in the US and his mentorship by an impressive array of anticolonial figures like Kwegyir Aggrey, CLR James, Nnamdi Azikiwe, and most importantly, George Padmore.

The second part follows Nkrumah as he returns to the Gold Coast to work as General Secretary of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) only to fall out spectacularly with the party. It follows the creation of Nkrumah’s own party, the Convention People’s Party (CPP), the harassment and arrest of the budding independence leaders by colonial forces, and the political struggle that all led up to the fateful independence day.

The final part covers Nkrumah’s time in office. His desperate attempt to maintain a fiercely anticolonial, anti-imperialist, and panafrican rhetoric while convincing first Dwight D. Eisenhower, then John F. Kennedy that he was no communist and that US funding of his beloved Akosombo Dam Project would not be against US interests. This section also covers the dangerous balancing act of Nkrumah in the Congo crisis and the tragic end of Patrice Lumumba. French also attempts to explain the domestic governance issues Nkrumah faced such as economic hardships occasioned by falling cocoa prices, his increasing authoritarian turn, and the numerous assassination attempts that left him paranoid and seclusive.

Many of Nkrumah’s adversaries blamed the nation’s economic woes on his interventionism – his desire to accelerate independence activism in other African colonies and to unite them with his fledgling political empire. Even to his many admirers on the continent, Nkrumah’s plan for a federation of African states was more panafricanism than they could swallow. Many were bewildered by his push for newly liberated nations to be united with Ghana regardless of geographic distance. But to Nkrumah, this was Africa’s only chance. Citing the United States of America, Nkrumah argued that creating a joint continental government was necessary before nationalist identities could calcify and make the project impossible.

But if Nkrumah was not overly ambitious with his panafrican project, Mr French certainly is with his attempt to fit such a complex subject as Nkrumah’s governance record into the final third of this book. Whereas he is incredibly meticulous in reconstructing Nkrumah’s life from available sources – crosschecking Nkrumah’s claims with independent sources and stripping his life story of the messianic qualities Osagyefo sought to portray – there is just not enough space for a similar kind of analysis for Nkrumah’s governance.

There is no doubt that Nkrumah was a visionary. His projects like the Akosombo dam, the Tema development, the motorway, and several state industries is proof that he was thinking decades ahead. But he was also a man that could only have been a creation of the times. In the 21st century Africa is not making its way into the speeches of US presidential candidates. African American activists are not lobbying for African development as an inextricable part of their own civil rights progress in the USA. Africa’s population, taken for granted their national identities and self-government, are way more concerned about finding their daily bread than examining their nation’s place in the global economic order. Perhaps most illustratively, the African Nationalist Congress (ANC) of South Africa, one of the last old school nationalist parties still active on the continent, has witnessed fracturing and in-fighting as day-to-day governance issues have overtaken the apartheid fight in the minds of a new generation.

Kwame Nkrumah’s independence speech ended with the electrifiying words “Today, from now one, there is a new African in the world!” Of that he was certainly right. There is a new African in the world. And even when it seems that the new African is more concerned with immediate material concerns; or fighting for their religious, ethnic, or partisan faction to get its share of the national cake; or even dreaming of giving up entirely on the continent and making a new life elsewhere; the new African will never accept the shackles of colonialism if they are ever faced with it. They were born free and will die free. And for that, they have Nkrumah and his contemporaries to thank.

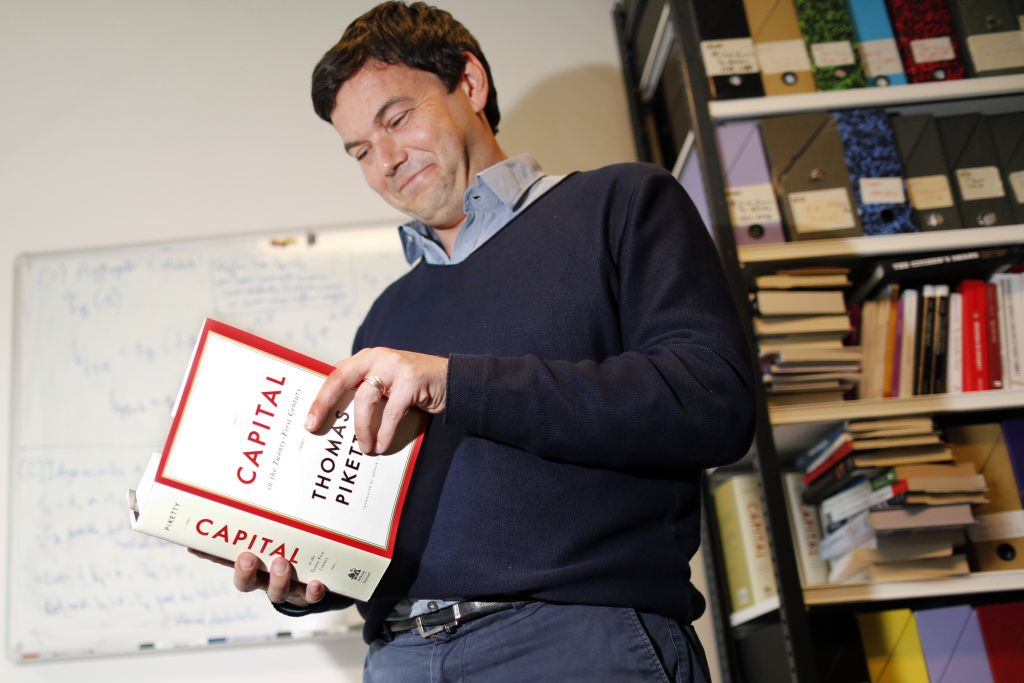

Thomas Piketty is a French economist and professor whose book, Capital in the 21st Century, published in French in 2013 and English in 2014, became an international bestseller. Piketty presents the most extensive review of wealth distribution ever attempted. Drawing from history and literature, he shows that the wealth of the world from antiquity has mostly been concentrated in the top centile (1%).

Thomas Piketty is a French economist and professor whose book, Capital in the 21st Century, published in French in 2013 and English in 2014, became an international bestseller. Piketty presents the most extensive review of wealth distribution ever attempted. Drawing from history and literature, he shows that the wealth of the world from antiquity has mostly been concentrated in the top centile (1%). Paul Krugman won the

Paul Krugman won the  With the party primaries of the NDC coming off on November 21, one cannot help but notice the several posters, banners and billboards bearing the faces and slogans of men and women hoping to get into or remain in parliament. There are several competitive match ups in the primaries that call for this level of campaigning however, the most visible campaign belongs to the contestant in the easiest primary race

With the party primaries of the NDC coming off on November 21, one cannot help but notice the several posters, banners and billboards bearing the faces and slogans of men and women hoping to get into or remain in parliament. There are several competitive match ups in the primaries that call for this level of campaigning however, the most visible campaign belongs to the contestant in the easiest primary race